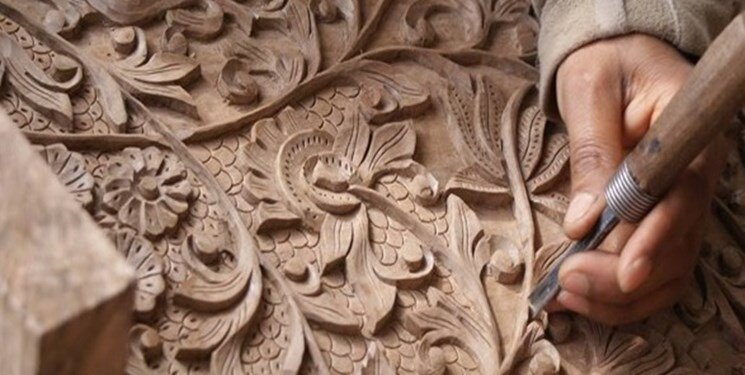

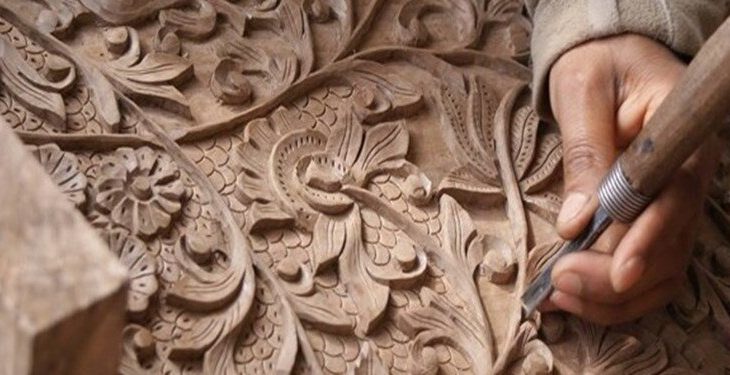

Wood Carving

Most Nepalese wood carvings are based on sacred texts and Buddhist or Hindu mythological architecture. Deities, religious icons, demons, animals, and other figures are all woven into the design. The sexier versions of these wood carvings can also be seen in the wooden roof beams.

In Lalitpur, Nepal, wood carving is a magnificent art form that results in wooden sculptures and works of art. The Malla and Lichavi eras are when the country’s traditional timber arts and structures first appeared. The medieval Durbar palaces and temples in and around Lalitpur and Patan’s Durbar Square feature exquisite wooden carvings.

Patan and the other two historic capitals of the Kathmandu Valley are exceptional examples of wood carving. Most of them are from the 17th to 18th centuries, while others are “younger” due to the restoration of many temples that were damaged in the earthquake of 1934. Patan has 136 monasteries and 55 temples, many featuring intricate carvings. There is so much to observe. All kinds of demons and multi-handed gods are frequent “heroes” of the painted beams and rafters.

The Newars are a major ethnic group of the Kathmandu Valley, and one of the attractions of the Newari towns—Patan, Bhaktapur and Kirtipur, in particular—is the beautiful handicrafts on display. Intricate wood carving, bronze religious statues, elaborately adorned pagoda temples, exquisite stone carving. Indeed, much of what is considered ‘typical’ Nepali craft and architecture is specifically Newari.

Most of these craft traditions are on prominent display around Patan. But less visible are the workshops in which finely crafted metalwork is made, tucked down dark alleyways and behind shops. Ducking beneath the low doorways, I found the workshop of brothers Badri and Kedar Tamrakar, whose name indicates that they work with copper.

They don’t only work with copper, though. In their small courtyard workshop, they also work with silver, brass and gold plating. They mostly sell their crafts to temples, and the gorgeous private shrine sunken at the basement level is a good indication of what they can make. They proudly showed me photos of the renovation work that they did at Indrachowk, a large and important temple in central Kathmandu, between 2006 and 2008—a sure indication that Badri and Kedar belong to one of the most skilled artisan families in Kathmandu. Much of their work is on a lesser scale, though prayer wheels made for Tibetan Buddhist temples, as well as the triangular metal flags that may be most familiar as the symbol of Nepal represented by the national flag.

Not all of the work they do is strictly religious, however. A new hotel in Kamal Pokhari, Traditional Comfort, commissioned the Tamrakars to create their metal fixtures. A highlight of the beautiful hotel is the rooftop area. You can sit and enjoy the view across Kathmandu beneath canopies emulating traditional temple architecture.

Visitors to Patan are welcome to drop in and see the craftsmen at work, whether alone or as part of a tour group. Head to the streets displaying the gleaming brass and copper religious statues and cooking implements, just off the busy Mangalbazar, and take a peek down the narrow alleys within and between buildings. You never know what you might find back there.